Where are all the containers? The global shortage explained

- Seydar Malik

- Aug 2, 2022

- 4 min read

Freight shipping is in the midst of a unique and unusual predicament. An unforeseen cascade of events caused by the pandemic has us facing a worldwide container shortage crisis. It’s a crisis because the lack of containers has a ripple effect down entire supply chains, disrupting trade on a global scale.

Where are all the containers?

So where have the containers gone? Many are in inland depots. Others are piled up in cargo ports, and the rest are onboard vessels, especially on transpacific lines. The largest container shortage is in Asia, but Europe also faces a deficit.

To grasp why the containers are where they are, it’s important to first understand the domino effect that has led to the present situation. Let’s start at the beginning.

Pandemic wave creates North American bottleneck

As the pandemic spread out from its Asian epicentre, countries implemented lockdowns, halting economic movements and production. Many factories closed temporarily, causing large numbers of containers to be stopped at ports. To stabilize costs and the erosion of ocean rates, carriers reduced the number of vessels out at sea. Not only did this put the brakes on import and export, it also meant empty containers were not picked up. This was especially significant for Asian traders, who couldn't retrieve empty containers from North America.

Then, a unique scenario developed. Asia, being the first hit by the pandemic, was also the first to recover. So while China resumed exports earlier than the rest of the world, other nations were (and still are) dealing with restrictions, a reduced workforce and minimal production.

A consequence of this is that almost all of the remaining containers in Asia headed out to Europe and North America, but those containers did not come back quickly enough. Massive workforce disruptions due to coronavirus restrictions in North America affected not only ports, but cargo depots all across the country as well as inland transport lines. Without adequate staffing, containers started to pile up. As borders tightened, customs became more complicated to clear as well, worsening congestion. In addition, there were rapid shifts in tradelane demands that were challenging for carriers to adapt to.

There was no time to clear the very large backlog of containers with limited workers before more started arriving. North America currently faces a 40% imbalance; which means that for every 100 containers that arrive only 40 are exported. 60 out of every 100 containers continue to accumulate, which is a staggering figure considering the China to USA trade route sustains on average 900,000 TEUs per month. That’s during a normal year; the current shipping volume is at record highs this quarter (up 23.3% compared to last year, according to Descartes Datamyne)

While continuously assessing the situation, it is evident that the transpacific volume from Asia headed stateside aren’t slowing, offering no recovery time. Why?

Carriers jump on lucrative transpacific profits

Container shipping rates have been surging on all East to West shipping routes since May, with the highest rate upturn hitting the transpacific. The Drewry World Container Index is currently at its highest in four years. Eastbound container freight rates have not just increased a lot since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak; they have more than doubled, eclipsing all historical highs. SE Asia to US rates have spiked from around $2,000 up to an eye watering $4,500 per 40ft container.

World Container Index Assessed by Drewry

Alphaliner reports that carriers can get 66 cents (per 40ft container per nautical mile) on the Shanghai to LA route against less than 10 cents on the return. Even better rates are on Shanghai to Melbourne with 88 cents, or Shanghai to Santos with 75 cents. The pressure is on to get containers back to Asia so that carriers can take advantage of these margins, empty or full. The Asia to US and Asia to Oceania trade routes have become so lucrative that carriers aren’t even waiting for cargo before sending containers back to Asia, especially when the cargo isn’t available at port.

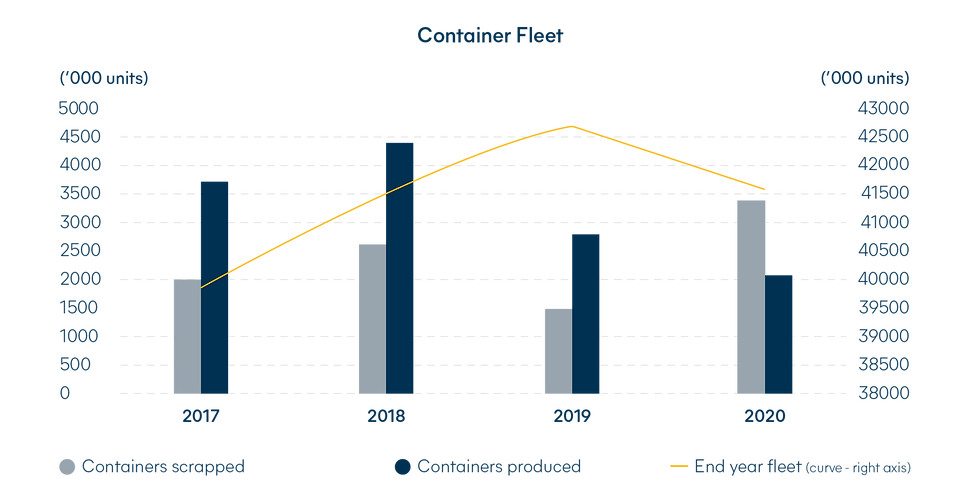

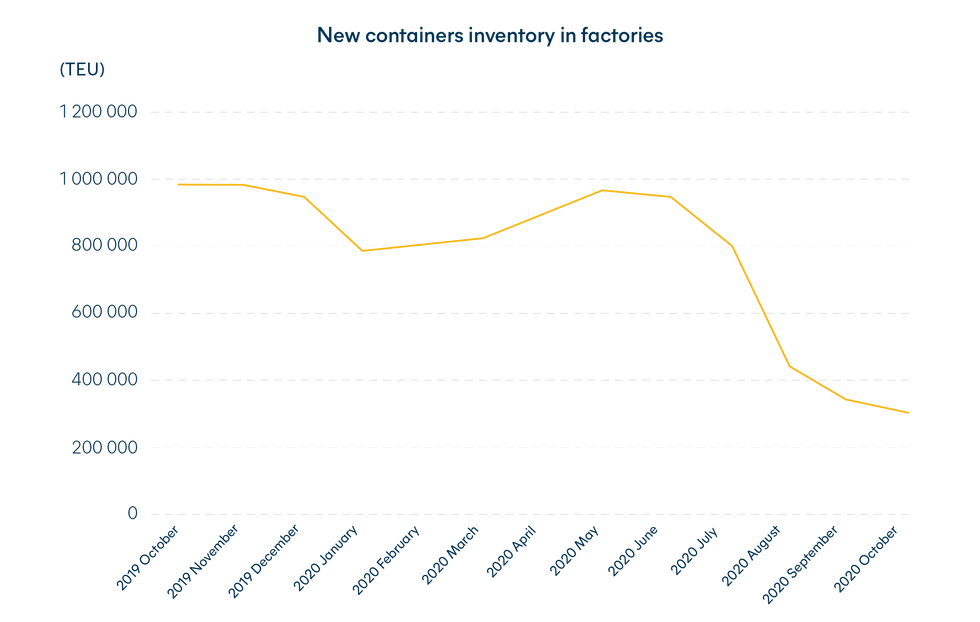

Global container fleet shrinking

Compounding on the shift in trade imbalances and bottlenecks is that production of new containers is woefully low. The rate was already down in 2019 and dropped even further this year, especially when demand fell dramatically in Q1 2020. The scrapping of containers now exceeds the building of new ones, causing inventories in factories to plummet. It will take months before more vessels and containers are built, meaning capacity likely won’t normalize until Q2 2021.

This limited access to available containers is also driving up the buying price of new containers, since manufacturers know demand is such that they can charge at a premium. Chinese container manufacturers, who dominate the market, now charge around $2,500 for a new container, up from $1,600 last year. Likewise, container leasing rates have rocketed, up by around 50% in the space of just six months.

The race for available containers

Needless to say, the lack of containers can’t satisfy current shipping demands, and we have a full-blown container crisis on our hands. Any available containers are booked out immediately, which is why we strongly urge our customers to book cargo as early as possible.

Although there are some measures underway to help resolve the deadlock, such as carriers attempting to reduce free time and detention period as well as more efficient unloading systems, realistically we won’t see the global container shortage crisis returning to normal for the coming months. Unfortunately, it’s also predicted that contract freight rates will remain high throughout next year.

How can Hillebrand support you in this situation?

We encourage you to cover your products with a shipping insurance, to ensure your peace of mind and be prepared to face any unexpected situation.

We understand the risks for your goods if delays occur at ports with high temperatures. In a situation of temperature-controlled containers shortage, we can help protect your wines and beers with our insulation liner which reduces temperature contrast to an average of 8-11 degrees Celsius.

Hillebrand has over 50 warehouses in main wine producing and beverage consumptions areas, where you can store your beverages and goods safely with our temperature-controlled facilities.

Comments